Life’s Most Important Lessons Aren’t Learned in the Classroom

During my elementary school years, I was fortunate that I didn’t face name-calling, teasing and bullying like many other kids with disabilities do at school. However, there was one incident that cut me to my core.

During my elementary school years, I was fortunate that I didn’t face name-calling, teasing and bullying like many other kids with disabilities do at school. However, there was one incident that cut me to my core.

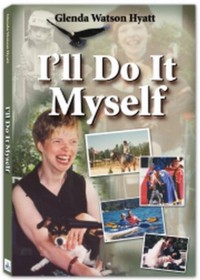

As I share in my autobiography I’ll Do It Myself:

Mom taught at my elementary school, so she would pick me up from my classroom at the end of the day and carry me out to the van at the front of the school; the school wheelchair stayed at school. One day, Mom had to stop at the office on our way out. She sat me down on the floor in the hall next to the gym doors at the main entrance. She would be only a couple of minutes, and I wasn’t in the way as people were leaving.

One boy, a year or two older than me, walked by and asked, “Are you retarded?†and then kept walking. I didn’t know what to say, and if I had said anything, my speech would have added fuel to the fire and would have confirmed his assumption. I said nothing.

Once Mom put me into the van, I burst into tears. When I managed to stop crying enough to communicate what had happened, Mom was sympathetic. She attempted to make light of it like she usually does, suggesting that next time I reply with something like, “No, are you?†– as if I could get that out clearly enough for it to be effective.

The incident was soon brushed off and forgotten – on the outside; but it wasn’t forgotten on the inside. That question hurt me to my core for a long, long time. Even though I knew I wasn’t retarded, I realized that others did see me as something I’m not. Since that day, I’ve been trying hard to prove to others that I’m not retarded.

Having reflected upon this over the years, I now see two issues here; the first being the word “retardedâ€. Several kids from the then Woodlands Institution were bussed to our school; many of them had mental retardation, as the disability was called back then. Looking back, I have no doubt that the boy meant no harm or ill-will. He asked a simple question. But, for me, “retarded†was a loaded word; it hurt, it degraded, it stung. Because of the use of the word through history, for many people with disabilities, being called retarded is as hurtful and demeaning as calling an African-American the n-word.

Ideally the word would vanish from our language. But, considering how pervasive the word is (how often do you hear someone utter something like “that is retarded†or “what a retard�), the word vanishing is not realistic, unfortunately. The next best option is to disempower the word for those who are negatively affected by it. The word has power only if we allow it to. I’m still sorting through how exactly do to that, which might make for a lively discussion in the comments below or a topic for a future post.

The second issue stemming from the incident was that my feelings weren’t acknowledged. A joke was quickly made and then the matter was brushed aside. No doubt that was easiest in that moment. When I’m upset and crying, Glenda-ish becomes even more difficult to understand. Having a deep conversation at that point was pointless. However, it meant my feelings were discounted.

A similar situation happened recently when Darrell was laying on an emergency room stretcher and wearing an oxygen mask because his pneumonia had worsen so much since our first trip to the ER four days earlier. Sitting at the foot of his stretcher, I was feeling guilty for not being able to make him the proverbial chicken soup or to raise him up high enough in bed. Perhaps if I had been able to properly care for my husband, then we may not have needed to call the ambulance to take him to the hospital where he was admitted for two weeks.

Irrational I know, but that was how I was feeling in that moment. While sitting there with Darrell, someone I love and respect, and whose profession is to comfort and counsel people in such situations, came to visit. Rather than acknowledging my feeling and proceeding from there, he reprimanded me for feeling that way. That day was the toughest one for me during the two-week hospital ordeal.

We don’t like seeing our loved ones hurt and upset; we’d like them to be happy all of the time. But, life sucks at times! To live a full life sometimes means, unfortunately, getting hurt, being upset, feeling down at times. Acknowledging those times, those feelings is how we can wholly and completely accept our loved ones. Sometimes acknowledging an owie exists is as important and healing as is gently covering it with a band-aid.

Previous miniseries post: Integration: Balancing Including the Child with Benefiting the Child

Next miniseries post: Coming soon!

If you enjoyed this post, consider buying me a chai tea latte. Thanks kindly.

Subscribe via RSS

Subscribe via RSS