The Early Years, The Therapy Years

I can now say I’m an internationally published writer! Reprint, with permission, from: OT Insight Vol. 28 No. 3 April 2007. Magazine of the New Zealand Association of Occupational Therapists (Inc).

Reflections – before you begin:

In this issue we are privileged to share an excerpt from the autobiographical writings of Glenda Watson Hyatt. We encourage all occupational therapists who read this article to use Glenda’s “lived experiences” to critically reflect on client-centred practice and the nature of occupational practice as we know it now, and in relation to that of yesteryear. Glenda provides us with a frank and open account of “what it was like” through the eyes of a young consumer of occupational therapy.

Many of you will identify with this piece of writing. Some may feel a little defensive, as our profession is not necessarily shown in a great light! After all, it does seem that the OTs were trying, but just didn’t get it right for Glenda. However you feel when reading this, hopefully you will use it for the opportunity that it brings to really listen to our clients’ stories, and to learn from their lived experiences. Such gifts as this help us to think about what therapy looks like to the recipient. Let us use our ability to reason interactively and conditionally. Let us focus on the person, not the component part of a task. Let us include the client in the reasoning process. Glenda’s experiences occurred some time ago – hopefully as a profession and as individual practitioners, we have moved on!

For further provocative reading, you might also like to visit the following website: http://www.disabilityisnatural.com

I entered this world one Friday morning in early November, 1966, in Vancouver, British Columbia. A light dusting of snow covered the ground. Mom said the North Shore Mountains looked like upside down pink ice cream cones as the sun rose outside her hospital room window.

Mom had a normal pregnancy, and everything was fine up until my actual arrival. Then the situation became somewhat scary and uncertain. Mom had a reaction to the Xylocaine epidural and went into convulsions. The doctor had to pull me out with forceps, which meant I didn’t have time to read the instructions on my way down the chute. I missed the fine print on needing to breathe immediately.

One doctor worked on reviving Mom, while another one worked on saving me. Luckily, a pediatrician specialist was just leaving the hospital and was called back to try to get me breathing. Perhaps it wasn’t a coincidence that the specialist was there at that particular moment. He was probably one of the angels sent to save me that day. It was touch and go for a while. Dad nearly lost both of us.

I definitely would not have held my breath for six minutes had I known what hassles it would cause for the rest of my life. Talk about learning from experience. You would think the first lesson for a newborn would be somewhat easier!

I was blue for a good part of my first day and was placed in the “no touch zone” as the intensive care nursery was called in those days. Only the doctors and nurses were allowed to touch me. Mom could only stand at the window and watch me. Apparently she would not go back to her room until she saw me move. She prayed hard that day that I would live. Live I did!

It was quite some time before I was officially diagnosed with cerebral palsy, or more accurately, cerebral palsy athetoid quadriplegia. The lack of oxygen had caused permanent brain damage, resulting in a lack of muscle control and coordination. My physical movements are jerky and involuntary; one body part or another is in constant motion. My left hand has some function, while my right hand is generally in a tightly clenched fist. I can’t walk without support, and my speech is difficult to understand. Finally, my head control is tenuous, and swallowing takes a conscious effort.

At six months of age, one doctor offered the opinion that I was mentally retarded and that I should be institutionalized. That would have meant a life with little or no contact with my family or the outside world. I would have received minimal education, living a life without hope or opportunity. Thankfully, my parents had their own unflattering opinion of that medical professional and did not follow his bleak recommendation.

At the age of two and one-half years, I started my school career at the Yellow Submarine, a special needs preschool at the University of British Columbia. One day, the psychologist, Dr. Kendall, came by to test if anything was going on in my damaged brain.

At that point in my life, my speech was very limited, consisting primarily of initial consonants and sounds. Going through the Peabody Vocabulary Picture Test, I uttered one response that he could not understand. Finally, in complete desperation, he called in Mom, who was observing from behind the magic mirror (actually a one-way window), to decipher what I was saying. Roo roo. The two of them gazed at the picture of a chicken. Roo roo. Suddenly it dawned on Mom. She asked, “Glenda, do you mean rooster?” Yes! The picture was obviously a rooster as it had a big, red comb. The experts expected me to offer the accepted response – chicken. Who was called mentally retarded?

Dr. Kendall reported that I was bright and showed potential. After all, I knew the difference between a chicken and a rooster before the age of three. Even with this encouraging report from the psychologist, I would be required to prove my capabilities and potential countless times throughout my life as so many people don’t see beyond the cerebral palsy to see me.

Following the only advice given by the doctor after my birth, my parents did take me home and love me. In the late 1960s, support was non-existent for parents who had children with special needs. My parents were left to figure out things on their own; they did the best they knew how at the time. Who could ask for more?

Mom was still completing her degree in education, with a specialty in Special Education – lucky me! Thus she had access to the medical library at the University of British Columbia, where she spent time reading about cerebral palsy and searching for answers to questions that could not yet be answered by the doctors.

Much of the time my parents muddled along, trying different approaches until they found one that worked. In the early years, feeding was definitely a major issue. Placed in the plastic cuddle seat on the table, I had a short attention span when it came to eating pabulum and other mushy baby food. I was either more interested in what was happening around me, or I was bored because it took so long to finish a meal. Dad learned to keep my attention while feeding me by sticking my favourite rattle, which had a suction cup, on his forehead. I doubt that idea was in a Special Ed textbook but rather an idea attempted out of sheer desperation!

Next was the high chair with a towel tied around my middle to hold me up. One time when Dad was feeding me, I picked up the spoon and threw it on the floor. Dad firmly said “No”, picked it up and placed it back on the tray. I did it again. Dad repeated his stern no. I did it again and, perhaps, again. Dad lightly smacked my hand. I cried. Dad went into his bedroom and cried. The incident taught both Daddy and his little girl that having cerebral palsy did not preclude me from discipline. That may have been the first incident of discipline, but it was definitely not the last!

As I grew and gained some hand control to do more than throw the spoon on the floor, I was able to feed myself, more or less. It was a slow process. I was nearly always left sitting alone at the table as I finished my supper. Some nights I exerted more energy than I gained by eating. It’s no wonder I was so skinny. The process wasn’t pretty, especially when I was tired, causing my involuntary movements to be even less controllable. Those mealtimes often resulted in a battle and tears at the dinner table. Perhaps this is why I’m still uncomfortable eating around others not close to me and try almost anything to avoid it.

When I graduated from my crib to my first bed, the bed was actually a mattress on the floor. At that time I was getting around by crawling on my hands and knees. By having my bed directly on the floor, I was able to crawl in and out of bed myself. Independence was important, even at a young age.

When we moved into a larger townhouse, I had my own bedroom with space for an actual bed. I was given the one Mom had as a child. To ensure the bed was still low enough for me to climb into by myself, Dad cut a sheet of plywood to lay across the bedrails, with the foam mattress on top. Who needs a box spring!

Beginning around the time of the Yellow Submarine and lasting for roughly a decade, I had therapy – physio, occupational and speech – several times each week. This was necessary to improve balance, muscle coordination and verbal communication. While therapy was necessary, it was seldom fun; like taking foul-tasting medicine.

Physio and occupational therapy involved monotonous tasks, such as repeatedly grasping beanbags and putting them in muffin tins, climbing up a few stairs to simply reach a brick wall, and being rolled around on a large, inflated ball or tube. This was all done stripped to my underwear. When I became older, I was permitted to wear shorts and a top.

In most cases, my therapists were not the brightest individuals. One day I came home from Kindergarten, nearly in tears. Mommy, my knees hurt. She sat me down and looked at my long-legged braces. The occupational therapist (OT) had put them on the wrong legs! Wearing shoes on the wrong feet causes some discomfort, but wearing heavy, metal braces on the wrong legs hurts. No doubt, I knew he was putting the wrong brace on the wrong leg. However, being nonverbal, I likely kept quiet, something I often did, because I thought he wouldn’t understand what I was saying, and I didn’t want to create a big hassle as he tried to decipher what I was telling him. After all, only people close to me understood Glenda-ish.

Feeding myself was always a struggle. The OT suggested that bending a spoon ninety degrees may make it easier for me to get the spoon into my mouth, a great idea. The next week, I took the spoon in my left hand, my only somewhat functional hand, and was all set to . . . feed the OT. He had bent the spoon the wrong way! Thankfully, it was not one of Mom’s good spoons.

In a similar attempt, he thought a swivel spoon might do the trick. This spoon had a large, plastic handle to grip and a spoon bowl turned ninety degrees, in the correct direction, which actually swiveled. Well, between my jerky, uncoordinated movements and this spoon swinging back and forth, the peas ended up across the room! I continued using a plain, unaltered spoon.

School was an older building; actually, it consisted of two buildings and a portable. The main building had four or five classrooms for the primary grades, the staff room, changing room and the principal’s office. The older kids were upstairs in the other building, accessible by a long, steep ramp.

As this was before integration and mainstreaming had been invented, all the Special Ed students went to this school, which was actually an annex of a larger school, several blocks away. This was definitely segregation. But, at that age, I didn’t know any differently. I was excited to be starting school with my new notebooks, crayons and lefty scissors. And, I do remember hating missing school when I was sick. It was so boring to stay home.

Being non-verbal, my teacher Mrs. Rutherford was concerned that she wouldn’t hear me when I needed help, so she gave me two small brass bells – I think they were her mom’s dinner bells – to ring to get her attention. It was soon discovered that the bells weren’t necessary as I was verbal enough to catch her attention when needed.

Because getting to the chalkboard was difficult for most of us once we were placed in our seats, we each had an 18-inch square piece of chalkboard at our desks for practicing our printing. It was also easier to work on a horizontal surface rather than a vertical one. Initially, my printing was wobbly scribbles. With practice and extreme concentration, I controlled my jerky movements enough to make my letters almost legible more of the time. I also kept a chalk eraser handy, though inadvertently an uncontrollable movement erased a good letter. In frustration, I did the letter again.

Although learning to print, and then to write, were important steps in learning to read, it was evident that printing would not be efficient. It took too much energy and was too time-consuming to keep up with my work, and that would only worsen through the grades. Learning to use a typewriter was a necessity.

An electric Smith Corona typewriter was placed at the back of the room, which a few of us shared. When it was time to do typewriter work, Mrs. Rutherford dragged me in my desk chair over to the typewriter table and then dragged me back to my desk when I was done. Then it was the next student’s turn. A while later, perhaps once funding became available, we each had a typewriter at a second desk beside us. We simply dragged the typewriter back and forth as we needed it. It was much easier, especially on Mrs. Rutherford’s back.

As I have only one somewhat functioning hand, I only typed with one hand, my left hand. While typing, I steadied my hand on the typewriter hood to give myself some control over the spastic movements and used my thumb to hit the keys, causing my wrist to be in a dropped-wrist position. This concerned the adults, particularly the physio and OT. Although this was decades before repetitive strain injury and carpal tunnel syndrome had been invented, they were concerned that the dropped-wrist position would cause damage over the long-term.

They decided a splint with a stick to hit the keys was needed to keep my wrist in a good position. With this contraption snuggly Velcro strapped to my arm, I was expected to have enough arm control to steady my hand mid-air, without resting it on anything, and to accurately hit the keys. And this was less frustrating than printing with a pencil? After a few days, the splint ended up in the back of my desk drawer, and I resumed typing with my left thumb, my hand in its compromising position. I type the same way today, as nothing else feels as natural. For a non-verbal individual who relies on written communication, my left thumb is my most valued body part.

My parents bought a Smith Corona typewriter for me to use at home. The OT suggested that a keyguard may prevent me from hitting multiple keys at once, and he offered to make it himself. Super. Months later he finished drilling the holes in a piece of Plexiglas. When installing the handmade keyguard onto the typewriter, it was discovered that there were more holes than keys! Another OT solution was tossed on the junk heap. Luckily, Smith Corona also made keyguards.

When I was ten or eleven, I had one OT who had me actually make things. She took me into the workshop and allowed me to use some of the tools. That was cool! I remember making a wooden doll bed. I even painted it, too. Then one day she told Mom, “Glenda figures out how to do things on her own, in her own way. She doesn’t need me. We are wasting her time here.” I finally had a therapist who made sense and actually understood me, and I had to let her go.

Physio and speech therapy also ended around the same time. I was at the age when I knew what I had to do in order to maintain the capabilities that I did have. Although the years of therapy are not among my fondest memories, I do realize it was necessary to maximize the mobility and functioning that I did have, and, for that, I am grateful.

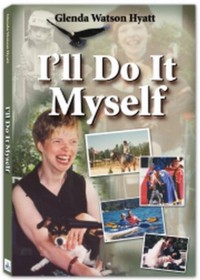

Excerpted and condensed from Glenda’s recently released autobiography ‘I’ll Do It Myself’, in which she intimately shares her life story to show others cerebral palsy is not a death sentence, but rather a life sentence. Copies can be ordered from www.doitmyselfblog.com.

Glenda Watson Hyatt

Glenda@BooksbyGlenda.com

Subscribe via RSS

Subscribe via RSS